Chandigarh and Brasilia

Chandigarh – designed by Le Corbusier –

and Brasília – designed by city planner Luis Costa and architect Oscar Niemeyer-

are master planned cities, created in the abstract, following a utopian vision. They would be cities of the future, free of the deficiencies that plagued cities of the mid-twentieth century, exemplifying aesthetic principles that reflect socially progressive political and philosophical ideologies, and embrace the technologies of the future – namely, the car. These cities began with grand abstract plans, promising the future, but both failed to reach their lofty goals in similar ways. They are cities designed from the top down, and cities tend to shirk these structures of order as they evolve over time, creating organic social formations when rigid plans become brittle and unsustainable.

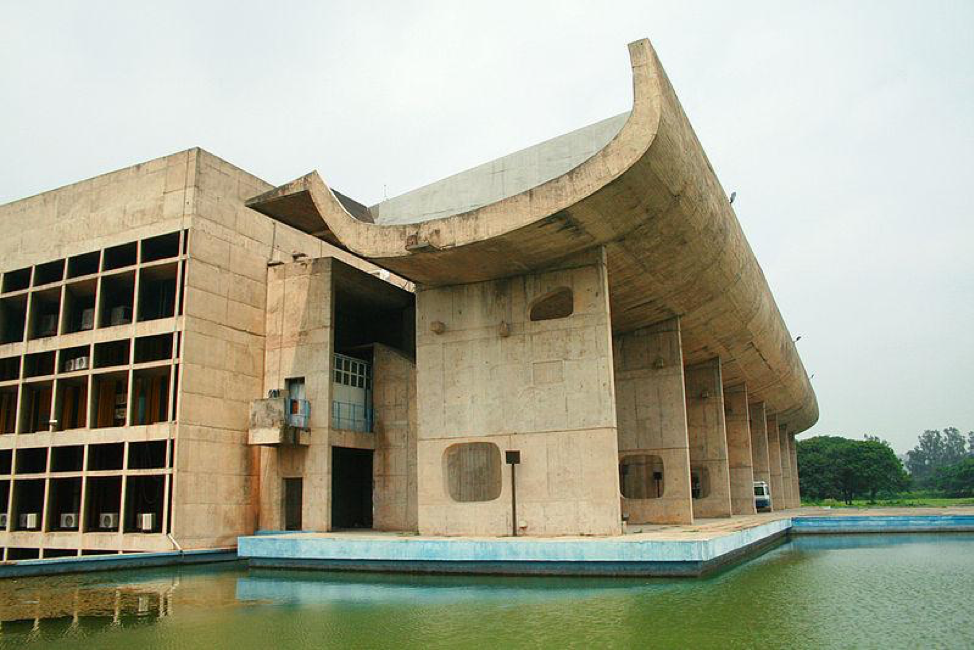

Le Corbusier was commissioned in 1951, by India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, to design the new capital city of the Punjab region.

Chandigarh would symbolize a nation forging a new identity free from colonial subjugation, unfettered by the constraints of tradition, and embodying aspirations for equanimity. Le Corbusier was the quintessential modernist architect, whose theoretical Radiant City garnered international influence and established a new paradigm for city planning and urban architecture. Chandigarh was designed to incorporate the ideas of the Radiant City and a ‘Garden City’ – a city without high-rises and equitable socio-economic conditions – on the template of a body.

The ‘head’ contained the capital complex for governmental functions, the ‘heart’ served as the commercial center, and the ‘arms’ which bisect the main axis housed industrial and academic functions on either side. The city is further divided into sectors that are intended to function as self-sufficient neighborhoods, incorporating shopping and community facilities. Buildings incorporate this balance in their design as well. Pragmatic and functional materials house open and light dwellings that are simple and utilitarian. Chandigarh is a city of structures and spaces that are grand without being ostentatious and vibrant without being gaudy.

Le Corbusier was under the spell of the car. He viewed it as the integral machine of the future, because it allowed for decentralized rapid transit. Thus roads are central design feature of Chandigarh. Traffic flows smoothly through the city across a symmetrical system roads, and there are numerous large parking structures to accommodate these mechanical residents. The city is scaled for the car as well. A car is an essential means to travel from one sector of the city to another. Although it is a city containing public spaces for people to mingle and coexist, it is not designed for the pedestrian. And although it is modeled on the human form, it is, ultimately, a city that fully embraces the centrality of the machine age.

Chandigarh was designed to embody a pragmatism that ostensibly defies social stratification, forging a new aesthetic-symbolic paradigm for urban environments according to egalitarian principles that would incorporate people, from diverse socio economic histories, industry, technology, and civic functions into a harmonious civil society. Since its completion in 1960, Chandigarh has become a India’s wealthiest city and its meticulously designed urban center is surrounded by sprawling villages, inhabited by poor immigrants from rural areas.

This is the economic disparity that Chandigarh was intended to overcome. In addition, as the city grew and evolved, it has remained rooted in the past, becoming a relic of a generation gone by. The urban fabric hasn’t evolved in step with the world outside. The strict urban design reflects a rigidness to change. It embodies a design that purported to have accounted for all the variables of urban life, but never materialized into the cosmopolitan urban center the Le Corbusier envisioned.

Brasília was also envisioned as an urban utopia. A new capital city for a new nation, exemplifying the ideals of a new government attempting to hurdle itself onto the world stage. Like Chandigarh, it would be a symbol of Brazil’s future. It would embody Brazil’s diverse heritage and people, while overcoming the social stratification and oppression that defined the colonial period. It would display the engenuity and beauty of a nation and a people that, now free from imperialism, are finally able to realize their true potential.

To some extent, Brasília is a marvellous success. It was a centerpiece of Juscelino Kubitschek promise to deliver “50 years of progress in 5,” and it was completed in just 41 months, from 1956 to 1960. Architect Oscar Niemeyer designed some of the most stunning monuments of the twentieth century, the paramount expressions of modernist architecture. The Cathedral of Brasília, the National Congress, and the Alvorada and Itamaraty Palaces are buildings that invert traditional architectural forms and are seemingly plucked from the future. And the city plan, conceived by Luis Costa, represents the ideals of urban design extolled by Le Corbusier find their most consummate form.

This plan itself, however, is both a point of eminence and deserved scrutiny. Drawing heavily on the ideas of Le Corbusier, Brasília was designed for the car. Cars travel with fluidly and efficiently, rarely having to stop or cross paths with another vehicle, along boulevards lined with high-rise office and residential buildings. Residents enjoy easy flow between spaces for work, leisure and recreation, and living.

Life in Brasília flows smoothly on a grand scale along two bisecting axes, anchored by the Monumental Axis with government buildings, and segregated by functions along the other. Brasília is a city like an ideal machine, with all moving parts working in harmony.

Despite the theoretical perfection of Brasília it is far from ideal. Contrary to its designers intentions, it is, like Chandigarh, characterized by economic stratification. Wealthy residents who enjoy bourgeois comforts in the center are served by poor residents in satellite cities. It has become a utopia for a select few, and represents a fantasy of civic life for those who live there. Without a diverse urban population interacting on a human scale, Brasília lacks a vibrant urban culture. It is, again like Chandigarh, a city that today feels more like a monument than an urban environment. A museum that is lived in and must be maintained, more for posterity, grandeur, and symbolism than for sustenance of life.

Chandigarh and Brasília are cities that tried to fix the forms of the future, as though the future were some conceivable point that we were moving towards and the city was an inert platform to deliver us there. But cities are not inert. A city is an interface of human activity, composed of myriad complex systems, alive with affective potentialities, and, like all complex systems, subject to entropy and change. Cities will be the locus of human activity and development in the future, and the city itself, as an entity, will shape and effect the evolution of humans. A master plan is design from above. Cities, however, grow from the bottom up, organically and non-hierarchically, like a rhizome – a complex and variegated system without a center. Chandigarh and Barsília did not embrace this and, so, stand as monuments to ideology, relics striving for utopia, beautiful fantasies that will forever remain unrealized.