NY/DF

Modern industrialized cities, since their emergence just a few generations ago, were beset by a fluctuating dynamic between chaos and control. Population growth, industrial development, and financial solvency, set the roots for urban centers around the world. Cities grew like flooding lakes, spilling over their boundaries, swelling beyond their limitations in a flurry of production, eventually sending waves of change to the surrounding territories. The modern city seems to be an incomprehensible confusion, impossible to make cohere into a single unifying narrative or definition. Modern cities are kaleidoscopic, an evolving menagerie, reflecting the multiplicity of its inhabitants, a dream world full of trap doors and secret passageways.

In the history of modern city planning this complexity has been perceived by some as an immense frustration, to be surmounted by structure and organized development. Two of the largest cities in the western hemisphere, New York City and Mexico City, both underwent huge population growth and material change in the first half of the twentieth century. The advent of the automobile along with huge population growth, created traffic congestion and crowded neighborhoods. These were problems that Robert Moses in New York City and Carlos Contreras in Mexico City, sought solutions for. They only perceived chaos in the densely populated neighborhoods, overflowing with people living in a patchwork of decaying building, struggling against streets choked with cars and vendors. The city was, in their eyes, full of discord, blight, and decay. Through civic projects, they endeavored to ease this bedlam into a state of tranquility.

Moses and Contreras, who both studied at Colombia University, envisaged quiet restful neighborhoods free of the bourgeoning vigor and disorder. In the emerging industrial west, the car appeared to be the machine the future. They were beginning to crowd the narrow roads of pre-industrial cities, still flowing with horse and buggy, trolleys, and bicycles. Urban planners were captivated by the modernist vision of Le Corbusier. In his ambitious models of modern cities, like the Radiant City, urban planners glimpsed visions of order, efficiency, mechanization, and a harmonious integration of modern technology with life. The automobile – the machine of the future – was at the center of life, and the road was the means of passage to a better, more harmonious life.

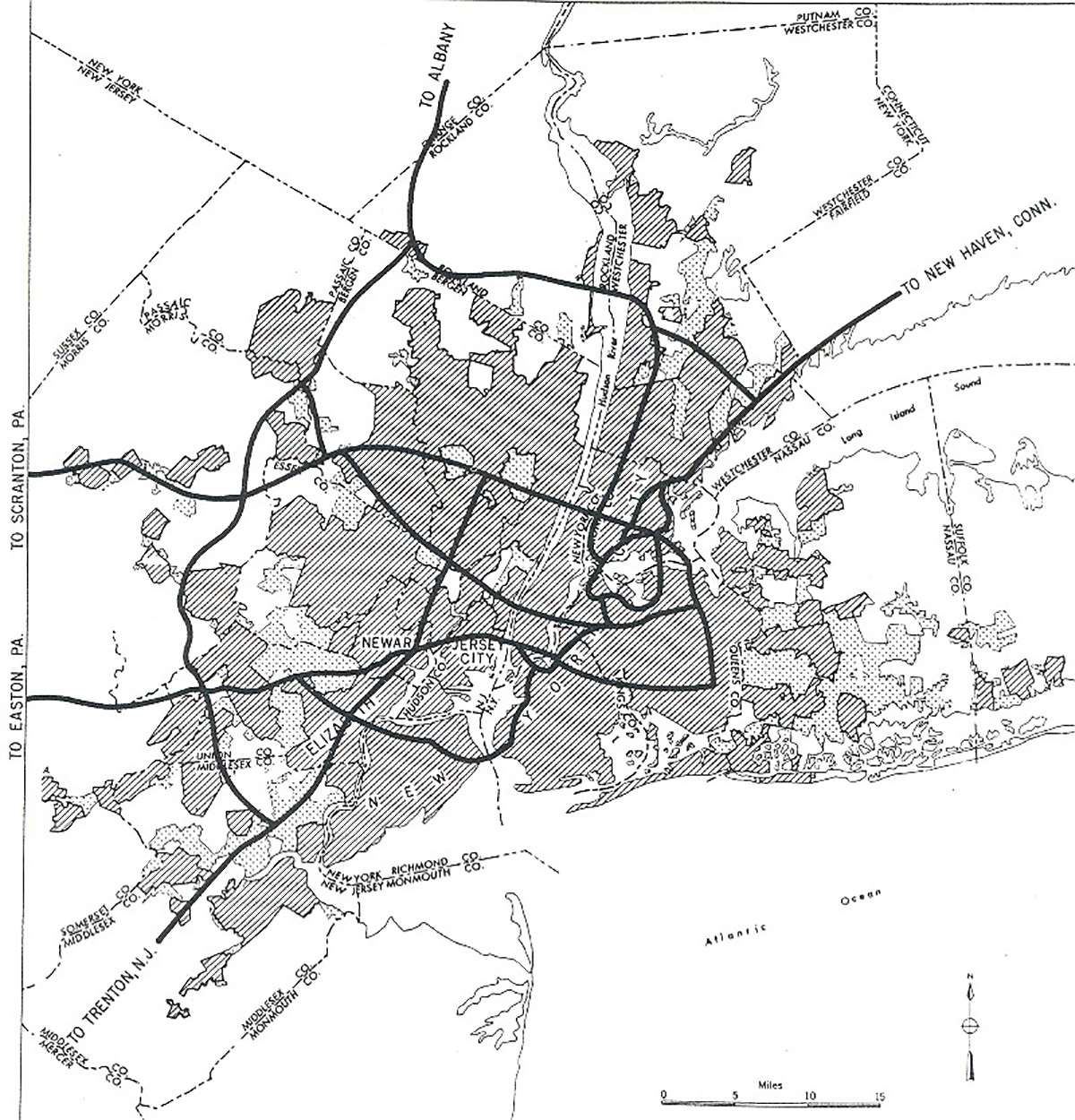

Robert Moses is largely responsible for the design of modern New York City that we recognize today. After the Great Depression in the United States, Moses lead many public works departments, wielding huge budgets that he mobilized toward the construction of highways, roads, bridges, tunnels, apartments, and parks. He transformed the city by cutting into dense neighborhoods with highways and boulevards, leading cars to the bridges and tunnels that would in time connect the boroughs to one another. Along many of these new roads, large housing projects with pristine green spaces were erected in the hope of replacing the chaos of neighborhoods with a placid mechanized order for the modern world.

The Cross-Bronx Expressway is one of Moses’s crowning achievements. An iconic exemplar of his vision for modern New York City. Constructed between 1948 and 1972, it traverses Manhattan Island, and was the first highway built in the United States through a densely populated urban area. The construction of this highway disrupted and altered thousands of lives in the Bronx, and, ultimately, transformed the flourishing culture of the neighborhood into place of crime and poverty. The expressway created barriers between people and cultures, lowered property values, and precipitated an exodus of its residents. In addition to the social distortions it created, the expressway failed to deliver the automobile traffic in the efficient manner promised. Today, the expressway is one of the most congested, despite its size, and most dangerous roads in the United States.

During the same period of time, Mexico City was also experiencing profound changes due to population growth along with technological and industrial development. New neighborhoods were growing, and the car was becoming the primary means of transportation from one to another. In 1925, Carlos Contreras proposed a plan for modern Mexico City that, he believed would, like Moses New York City, subdue the distasteful anarchy of the city. Two major road projects, Anillo Periférico and Viaducto Miguel Alemán, were design to move traffic through the city efficiently and create neighborhoods of order. Periférico was designed as a ring around the city that would connect peripheral neighborhoods and stem the growth of new ones. While Viaducto would serve as a central artery across the city. Construction of these roads did not begin until the 1950’s and 60’s, and it did not follow Contreras’s original plans. These roads were eventually constructed following buried or enclosed rivers. They became important arteries for traffic in a quickly developing city.

Periférico and Viaducto, like the Cross-Bronx Expressway in New York, served a functional purpose. They were a designed to connect and ease traffic congestion at a time when the car was ostensibly the way of the future. Today, the car is, despite its predominance in urban centers across the world, a blight on the dynamics of urban life. They contribute to pollution, the disruption of local neighborhood cultures, noise, and physical danger and harm. Periférico and Viaducto are now, like so many large roads in urban centers around the world, congested, confusing, and dangerous arteries.

In cities where everyone needs to move to survive, we cannot all move with a car for each of us. This was the vision of Le Corbusier and many other modernists of the time. For them, a car for every person, as opposed to mass transit, would enshrine a city of tranquility and order. The reality has been, for the most part, just the opposite. A century of design centered around the car has revealed the shortcomings of this individualistic, machine driven design. We have learned that, rather than resisting the organic dynamics of human life, the city must be designed in a way that embraces them, even when they are a chaos of complexities.